By Ben Kane, Programs Assistant

A new Fast-Response Cutter (FRC) named after fallen servicemember DC3 Nathan Bruckenthal is set to be put into service in July 2018. The purpose of the FRC is to serve as a patrol vessel and carry out ship boardings, coastal security missions, search and rescue missions, and general national defense missions. The naming of this FCR after Bruckenthal continues the Coast Guard tradition of naming these ships after Coast Guard enlisted heroes. The naming of this particular cutter after Bruckenthal was announced by Admiral Robert Papp, the Commandant of the Coast Guard, on the 10th anniversary of Bruckenthal’s death.

Nathan was born on July 17, 1979 and grew up in Stony Brook, New York. After a period of service with the Ridgefield Connecticut Volunteer Fire Department following his high school graduation, he joined the Coast Guard in 1998, quickly demonstrating his talent and commitment to his country. In his spare time, Nathan volunteered for a variety of tasks to help the local Native American reservation where he was stationed. Nathan volunteered as a police officer, firefighter, EMT, and assistant high school football coach – demonstrating his love of the country, its citizens, and his willingness to serve and improve his community. Following several years of commendable service while stationed in New York, Virginia and Washington State, he began serving in an elite tactical law enforcement program. In recognition of his talent during his service, Nathan Bruckenthal was among the first Coast Guardsmen chosen to be deployed to Iraq in 2003 during Operation Iraqi Freedom.

His responsibility during the conflict was to help patrol the North Arabian Gulf and conduct safety and security searches on vessels. The searches began as early as the morning after the initial naval bombardment of Iraq, when Bruckenthal and his team boarded a group of tugs who said they were stranded. The ships were found to contain a supply of automatic weapons and sea mines, and the Iraqi military personnel were arrested. After more patrols, boardings and trainings, Bruckenthal decided to remain in the Gulf for a second tour of duty.

One of Bruckenthal’s responsibilities was to instruct navy personnel on how to best conduct maritime operations. During a standard patrol of an important oil terminal in April 2004, several local fishing vessels approached and were turned away from the area by the U.S. forces. However, one vessel ignored the warnings, approached the oil terminal, and prompted servicemembers, including Bruckenthal, to board the ship. The insurgents aboard the ship, knowing they would not be able to proceed to their destination, detonated the explosives in the cargo bay of their ship, resulting in an explosion that fatally wounded Bruckenthal. Thus, Nathan Bruckenthal became not only one of the first Coast Guardsmen to serve in the Iraq war, but the only Coast Guardsman to die in the Iraq War or in any conflict since the Vietnam War. The actions of Bruckenthal and his men prevented the terrorists from approaching and harming the men on the nearby U.S.S. Firebolt, the oil platform and the oil terminal. As a result of his sacrifice, Bruckenthal was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star medal with Combat “V” for Valor, the Purple Heart, his second Combat Action Ribbon, and the Global War on Terrorism Expeditionary Medal.

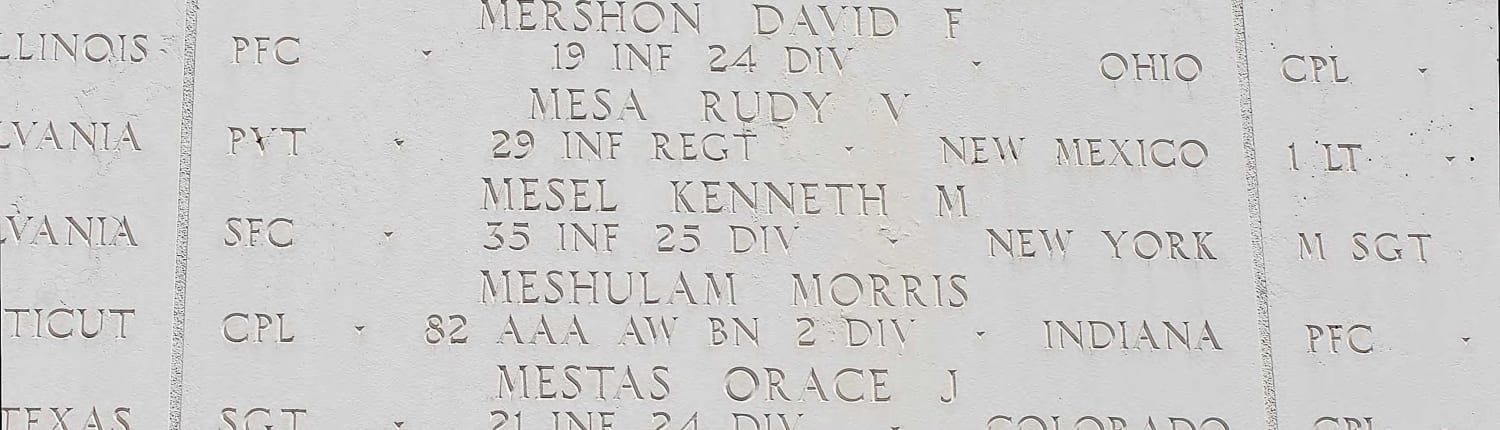

As a testament to the respect and love that Nathan’s friends, family, and fellow servicemembers had for him, several other buildings, scholarships, and plaques have been named and placed in his honor. Among other honors, the barracks where he first served has been renamed in his honor, and a non-profit baby pantry was established to provide aid to military and civilian employees in Baltimore. In addition, a fund, originally established to ensure his family would be cared for, has since been able to donate to causes like the Wounded Warrior Project, the Coast Guard Foundation, and Brooke Army Medical Center’s Center for the Intrepid.

Nathan Bruckenthal left behind a pregnant wife who gave birth to their daughter, Harper Natalie Bruckenthal, in November 2004. DC3 Bruckenthal’s sacrifice for the sake of the United States and in defense of his fellow countrymen serves as an example for all who choose to enter the armed services. We invite all members of JWV to come to the USCGC Nathan Bruckenthal’s commissioning on July 25, 2018 in Alexandria, VA. We hope to see you there.

Volume 72. Number 2. Summer 2018