Post: North County Post 385

Military Service: U.S. Navy

Member Since: 1974

1. Where and when did you serve in the military?

I enlisted in the Navy in my hometown of Chicago under the delayed entry program in 1973 and reported to Naval Recruit Training Center in Orlando in May of 1974.

After boot camp, I was assigned to Naval Air Station, Memphis.

In Boot Camp, the detailer asked me what I wanted to do in the Navy. I thumbed through the ratings handbook and chose Torpedoman’s Mate. The detailer said angrily, “That’s not open to women yet, but I’ll send you to a base that has a torpedo shop where you learn on the job.”

So he sent me to a naval air station where there wasn’t a torpedo.

While at Memphis, I applied three times for Torpedo School. Twice my request came back, “Request Denied – Rating not open to women.”

Undiscouraged, I applied again and the third time was the charm. The woman Personnel man who had become my friend called me at the barracks. “Paula, you have orders,” she said excitedly, “You’re going to basic electricity school at Great Lakes and then TM school in Orlando.”

I became the third female Torpedoman’s Mate in the Navy.

After finishing my schools, I was sent to the Mark 37 wire guided submarine torpedo shop in Groton, Connecticut.

I stayed there until I re-enlisted for SUBROC school, becoming the first woman to receive this training and finished my enlistment as a TM2 (E5) at Naval Magazine, Guam.

Women were not on ships in my day. My assignments were at shore torpedo intermediate maintenance facilities.

I was always the only woman TM, so I constantly had to prove myself, but I was determined to earn the respect of my male peers. I worked hard and studied diligently for the advancement tests. Finally, when I made E4, I felt I was accepted and had proven to myself and the Navy that women could do anything!

2. Why did you join the military?

I loved military and naval history. The first non-fiction book I read was in 4th grade. It was “The Longest Day” about the D-Day Invasion. From then on, I was hooked. I knew I wanted to be sailor!

3. How did your Jewish faith impact your time in the service?

At Boot Camp, I attended Friday night Shabbat Services. A JWV member was there and signed us all up.

Upon orders to each new base, I contacted the local Jewish community center to find a rabbi and services. I kept Kosher as often as I could. The Jewish Welfare Board provided me with canned kosher food and anything I needed.

Two Jewish Chaplains crossed my paths, Rabbi Bruce Kahn at NAS Memphis and Rabbi Botnick at Great Lakes. They nurtured me, inspired me, and left an indelible spiritual treasury in my life.

4. Have you ever experienced anti-Semitism at home or abroad?

While in the Navy, a thief used to break into my locker and steal my kosher food, but that could have been a statement about my gender, not my ethnicity.

After the Navy, while attending New Mexico State University on the GI Bill, I formed a Hillel group to change the name of the yearbook, which was called Swastika, a supposed reference to Native Americans of the era, but totally unacceptable to us. Our local synagogue, JDL in Denver, and JWV joined us in our fight to change the name. I wrote an article for JWV about the struggle for an issue of “The Jewish Veteran.”

Several times throughout my 30 years of teaching high school history, students have written ethnic slurs and drawn swastikas in their notebooks. I designed a Holocaust course in my district to address this ignorance.

5. Why did you join JWV?

It was a safe and loving place to be Jewish!

6. How would you improve a current JWV program, or what type of program do you think JWV needs to add?

I have no idea which members of my shul in Pomona, CA are veterans. I would like to be able to swap sea stories. Maybe recruiting at synagogues would be good project. I would like to connect nationwide with other female JWV members.

7. What is your favorite Jewish food?

Challah. I am never without it on Shabbat!

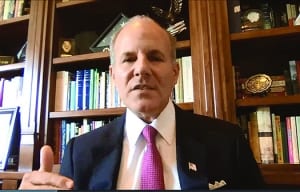

At our first business session, more than 100 members tuned in as the Israeli Ambassador to the United States Ron Dermer joined us for a question and answer session. Dermer spoke about the recent diplomatic breakthrough between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, saying he believes this is only the beginning. He thinks other countries in the Middle East will find it vital to work with Israel in the near future. “I think to the extent that you have leaders in the Arab world who would like to propel their countries forward and to be a force for modernization, then I think working with Israel is very important.”

At our first business session, more than 100 members tuned in as the Israeli Ambassador to the United States Ron Dermer joined us for a question and answer session. Dermer spoke about the recent diplomatic breakthrough between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, saying he believes this is only the beginning. He thinks other countries in the Middle East will find it vital to work with Israel in the near future. “I think to the extent that you have leaders in the Arab world who would like to propel their countries forward and to be a force for modernization, then I think working with Israel is very important.” Approximately 100 members also joined our third business session to hear a discussion on anti-Semitism with American Zionist Movement President Richard Heideman and U.S. Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Anti-Semitism Elan Carr.

Approximately 100 members also joined our third business session to hear a discussion on anti-Semitism with American Zionist Movement President Richard Heideman and U.S. Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Anti-Semitism Elan Carr. Carr also noted that while it’s obvious the internet and social media did not cause today’s anti-Semitism, “It is carrying this contagion further and faster than we’ve ever seen before and it is one of the chief reasons we’re seeing anti-Semitism rise today.”

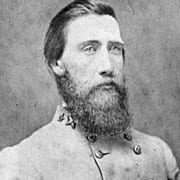

Carr also noted that while it’s obvious the internet and social media did not cause today’s anti-Semitism, “It is carrying this contagion further and faster than we’ve ever seen before and it is one of the chief reasons we’re seeing anti-Semitism rise today.” The official opening of Camp Hood took place on September 18, 1942. It is named for the commander of the Confederate Texas Brigade, General John Bell Hood. It was renamed Fort Hood in 1950. Today it is the largest Armored Post in the U.S. Army.

The official opening of Camp Hood took place on September 18, 1942. It is named for the commander of the Confederate Texas Brigade, General John Bell Hood. It was renamed Fort Hood in 1950. Today it is the largest Armored Post in the U.S. Army. At the request of the Columbus Rotary Club, the Army honored Brig. Gen. Henry Benning when it opened Camp Benning in 1918. It was renamed Fort Benning in 1922. In 2005, Fort Benning became the home of the U.S. Army Armor Center and School.

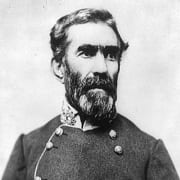

At the request of the Columbus Rotary Club, the Army honored Brig. Gen. Henry Benning when it opened Camp Benning in 1918. It was renamed Fort Benning in 1922. In 2005, Fort Benning became the home of the U.S. Army Armor Center and School. Fort Bragg opened in 1918. The local chamber of commerce named the Fort after General Braxton Bragg, the only general from North Carolina during the Civil War. Since the U.S. Army was concerned with mobilizing troops for World War I, they just let locals choose the name. It is now home to the U.S. Army Forces Command, XVIII Airborne Corps, U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 82nd Airborne Division, and many other commands.

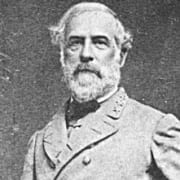

Fort Bragg opened in 1918. The local chamber of commerce named the Fort after General Braxton Bragg, the only general from North Carolina during the Civil War. Since the U.S. Army was concerned with mobilizing troops for World War I, they just let locals choose the name. It is now home to the U.S. Army Forces Command, XVIII Airborne Corps, U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 82nd Airborne Division, and many other commands. General Robert E. Lee was a West Point graduate and the leader of the Confederate Army. The U.S. Army named Camp Lee after him on July 15, 1917 during the mobilization for World War I. In 1950 it was renamed Fort Lee. Today Fort Lee is home to the Combined Arms Support Command.

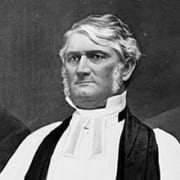

General Robert E. Lee was a West Point graduate and the leader of the Confederate Army. The U.S. Army named Camp Lee after him on July 15, 1917 during the mobilization for World War I. In 1950 it was renamed Fort Lee. Today Fort Lee is home to the Combined Arms Support Command. Camp Polk opened in 1941 and was named for Leonidas Polk, a West Point graduate, planter, slave owner, and Episcopal bishop who began the Civil War as a major general in the Confederate Army. It was renamed Fort Polk in 1955 and is now home to the Army’s Joint Readiness Training Center.

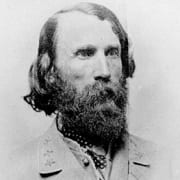

Camp Polk opened in 1941 and was named for Leonidas Polk, a West Point graduate, planter, slave owner, and Episcopal bishop who began the Civil War as a major general in the Confederate Army. It was renamed Fort Polk in 1955 and is now home to the Army’s Joint Readiness Training Center. Camp Gordon, named for Lt. Gen. John Brown Gordon, a native Georgian, soldier, legislator, and businessman, opened in July 1941 as a World War II training camp for the 4th and 26th Infantry Divisions, and the 10th Armored Division. It became Fort Gordon in 1956. The facility is now home to the U.S. Army Signal Corps and Cyber Corps.

Camp Gordon, named for Lt. Gen. John Brown Gordon, a native Georgian, soldier, legislator, and businessman, opened in July 1941 as a World War II training camp for the 4th and 26th Infantry Divisions, and the 10th Armored Division. It became Fort Gordon in 1956. The facility is now home to the U.S. Army Signal Corps and Cyber Corps. Fort A.P. Hill is a training center which opened in 1941. All branches of the U.S. Armed Forces train there. It is named for Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill.

Fort A.P. Hill is a training center which opened in 1941. All branches of the U.S. Armed Forces train there. It is named for Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill. Camp Beauregard, named for Confederate Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, opened in 1917 and today serves as a training facility for the Louisiana National Guard.

Camp Beauregard, named for Confederate Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, opened in 1917 and today serves as a training facility for the Louisiana National Guard. Fort Pickett is a Virginia Army National Guard installation which first opened in 1941 as Camp Pickett and renamed Fort Pickett in 1974.

Fort Pickett is a Virginia Army National Guard installation which first opened in 1941 as Camp Pickett and renamed Fort Pickett in 1974. Fort Rucker, named for Col. Edmund Rucker, opened in 1942, and serves as the primary training base for Army Aviation. He is the only Confederate below the rank of general officer with an Army facility named after him.

Fort Rucker, named for Col. Edmund Rucker, opened in 1942, and serves as the primary training base for Army Aviation. He is the only Confederate below the rank of general officer with an Army facility named after him.