JWV Member Chosen to Become Hologram in the Shoah Foundation’s New Project

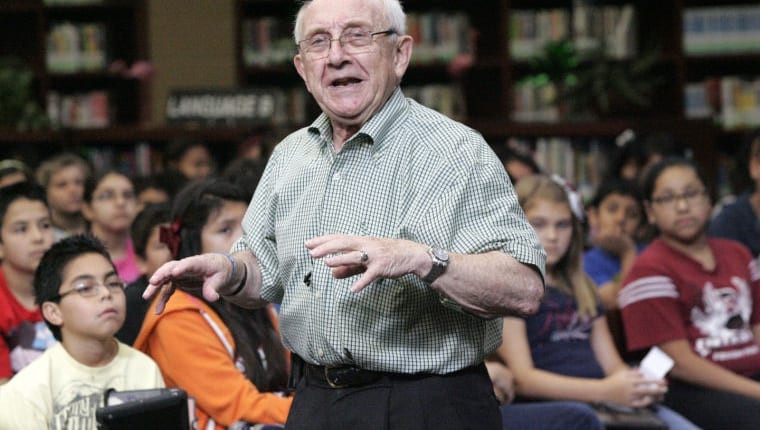

Max Glauben Speaking at Texas A & M. Photo Credit – Texas A&M Hillel

By Anna Selman, Programs and Public Relations Coordinator

For JWV members going to the opening night of the Dallas Holocaust Museum next year, they will see a familiar face. That is because JWV Member Max Glauben was chosen by the Dallas Holocaust Museum and the USC Shoah Foundation to be the face of their new interactive Holocaust exhibit.

“They’ll get to have a conversation with Max,” says USC Shoah Foundation Program Manager Kia Hays, “to maybe ask Max a question they might have had about the Warsaw ghetto after going through that or they might have had about the camps, or survival or coping…and get an answer and really connect with him on a very personal level.”

Glauben, born in Warsaw, Poland, survived the Warsaw Ghetto, multiple concentration camps and the death march as a young teenager. Since coming to America, he has committed his life to telling his story to ensure that the Holocaust is never forgotten.

“I have devoted my retirement to telling my story, and starting the seed for the Holocaust Museum that is scheduled to be finished next year around September 2019. It is going to be a fine museum with, of course, the Hologram Exhibit that was made with the USC Shoah Foundation,” said Max.

Glauben is one of the few remaining Holocaust survivors living in Dallas. As with most Holocaust survivors, Max is realizing that there will be no one else to tell their story after he is gone. This new innovative project will allow students to interact with a life-like hologram that hopefully give the students the ability to speak with a holocaust survivor.

However, he also visits schools as a Jewish War Veteran. “I come to speaking events when asked because I am a Jewish War Veteran. I love going to the schools and speaking with the children to tell them about my service,” said Max.

He was drafted during the Korean War in 1951. Max served for the next four years in different locations state-side as a mess hall sergeant.

Max Glauben being filmed for project. Photo Credit – Texas Jewish Press

“When I was liberated, the Americans gave us uniforms and had us help out. While I was at the DP camps, I would run the mess hall and I would drive the cars. So, I had a little experience coming. When I came to the states in 49, I registered for the draft and I was picked up in 1951,” said Max.

“I remember running the mess hall. I had the walls painted and had pictures of Mull Mullens up on the walls. At Fort Hood, I was awarded for the best mess hall. I don’t think anyone knew I was a Holocaust survivor. I just went with the flow. In those days, being a Holocaust survivor didn’t mean much, but I didn’t want to be treated any differently. I just wanted to be a normal person; I didn’t want anyone to feel sorry for me,” said Max.

“When I came to the country, I was not a citizen. I was grateful for what I did, and I became a patriot to the United States. They gave me citizenship. I feel that if you live in a country, and you should love that country and the people in that country. I honored my commitment to the country that saved my life, and I feel good and I don’t care how anyone else feels about that.”

Max is now able to go back to the places that he served in order to tell his fellow soldiers about his experiences.

“I went to Fort Hood and Fort Sill for their Holocaust remembrance ceremonies a couple of years ago. I think it is important to tell our military about the Holocaust. They incorporate some of the things we went through into their practice about how they should handle certain things,” said Max.

“I think it is important what myself and the other holocaust survivors are doing right now. We need to fight hatred, bigotry and racism,” said Max. “We need to ensure things like freedom of speech, freedom of religion are not broken. Unless we tell the people like it is and how things can change rapidly if we act the way we are acting right now, what goes around comes around…but you never know,” said Max.

Volume 72. Number 3. Fall 2018