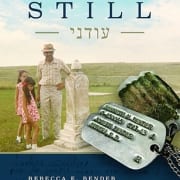

A Closer Look at “Still”

By Rebecca Bender

At a 70th anniversary commemoration of the D-Day invasion at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, I read excerpts from a book my father and I wrote together. My father, Kenneth Bender, participated in the D-Day invasion, and received both a Silver Star and Purple Heart during World War II.

“Still” is a book about five generations of my family, the Benders. It covers more than 150 years during which the family migrated from Odessa, Russia, to North Dakota, and eventually Minnesota. Included in the story is my father’s recollections about himself and his war service as just one of more than half a million Jewish servicemen and women in World War II.

Near Cardiff, Wales, June 1944

It was two a.m. when Kenneth heard an unexpected knock on the door of his barracks. “Captain Bender, Sir!” There was some urgency in the messenger’s voice.

Captain Bender had been training in Newry, Northern Ireland, with the two hundred men in his unit for a few months. Company B’s barracks were on the second floor of an old abandoned concrete mill. The men practiced hand-to-hand combat drills in a greyhound dog racing enclosure and hiked up and down Camlough Mountain, where even the big rocks they walked on sank into the boggy ground with just one step. They were continuing their preparation to invade Norway…

Bender’s focus and the focus of the men under his command had been Norway for almost two years… Then the plans abruptly changed… and the entire division had been relocated to Wales. Bender had been told of the new mission — training for an amphibious invasion of Europe to fight the Nazis on the ground. He had been informed of the timetable and the plan to leave for Omaha Beach within the week, but the knock on the door of the barracks woke him with a start. “Captain Bender, Sir!” said the messenger again. “I have a message from headquarters… “Sir, you and all the men in your unit who are Hebrews are supposed to get dressed and come to the officers’ tent in fifteen minutes.”

“Thank you, private,” said Captain Bender.

Bender quickly dressed, grabbed the list of two hundred soldiers under his command, and walked swiftly to the enlisted men’s barracks. He walked in and yelled, “Attention!” The men all stood by their bunks at attention. Captain Bender continued, “I will now call out names of some men, and I want you to get dressed and meet me outside the officers’ tent in ten minutes.” He started calling out the names of the Jewish soldiers. “The rest of you can go back to sleep. That is all.”

Captain Bender went to the officers’ tent and waited outside for his men. Standing in the coolness of the Welsh night, he thought back about telling his family that he knew volunteering as a private in the infantry was the right thing to do, even though he had graduated from law school just two years before and was working as a lawyer in Rapid City. But why were the Jewish soldiers in his unit being singled out…

The Jewish men of his unit had lined up silently behind Captain Bender. The Captain led them into the tent. “Captain Bender reporting, Sir.”

“At ease, men,” said the officer. The officer broke the anxious silence:

Gentlemen, we have been sent by Company Commander, Captain Keith Schmedeman. Captain Schmedeman has learned reliable information from the front lines, in North Africa and Italy, about how Hebrews, people of the Jewish faith, are being treated by the enemy once they are captured. The Axis are not taking the Hebrews as prisoners of war. They are shooting them on the spot. This has come down from high up. If they see that your dog tags have an “H” for Hebrew, they will kill you or torture you until you die.

The Lieutenant here has a machine that can change your dog tags — you can either switch them from H, to P for Protestant or C for Catholic. When you change your dog tags, you will have a better chance of surviving the war. Now, line up behind Captain Bender to get your dog tags changed. Captain Bender, tell the Lieutenant if you want a C or a P on your tags. Once you have completed this process, you are dismissed.

Captain Bender moved up across from the Lieutenant sitting with the machine, who had his hand out to take the Captain’s dog tags. Kenneth’s twenty-eight years of life passed before him, as is supposed to happen when you see a car heading straight towards you on the road. But Kenneth Bender didn’t see headlights. He saw his Grandma Becky’s face — stern, wise, and warm all at once. “You are born a Jew, and you will die a Jew.” He knew what she meant. No matter what happens in between, once you are born as a Jew, you are who you are. You carry the joys and responsibilities of your religion. You carry the history of your people.

Each soldier had two metal tags around his neck, listing next of kin and religion. One of the tags had tape on it, so the enemy could not hear the American soldiers approaching due to the clanging of the two tags. If a soldier was killed, one tag would be removed and the other would remain with the body. …

“P or C ?” The Lieutenant’s words brought him back to the mo¬ment. In the quiet of the tent, Captain Bender felt his words come from deep inside of himself, calm and confident.

“Sir, I will not make the change.” Captain Bender then told the men assembled that they had the option to do as they wished, and he started to walk towards the exit of the tent. That’s when he heard Private Feldman, “Sir, I will not make the change”; then Private First Class Skurmann, “Sir, I will not make the change”; and on and on, like a rolling echo in a tent covered with burlap, that would not naturally lead to the phenomenon of an echo. These were man-made echoes. These were echoes that came from thousands of years of faith.

Volume 74. Number 2. 2020